the rise of botox and filler, changing beauty standards, and decentering the male gaze

🤎this week on the Spoiled Girlie Support Group🤎

the TRAD HUSBAND to FAMILY ANNIHILATOR pipeline

📖besties book club📖

The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin

🍵the tea🍵

the rise of botox and filler, changing beauty standards, and decentering the male gaze

Society’s obsession with women’s looks is about as pervasive as it is damaging. From a young age, girls are bombarded with messages that their worth is closely tied to their appearance. And with social media and the growing digitalization of the world, these messages only hurl themselves towards impressionable girls faster than we can teach how to critically sift through them.

Earlier this month, this following tweet (oops, X post) stirred discussions online:

For those whose internet decided to fail them and load the image way too slowly, the post reads: Past time to ban fillers in England (none of these women are close to 30). It also features three photos of women who, despite their undeniable beauty, still fall victim to the world’s impossible standards. All because they look “older than they really are,” thanks to the botox, fillers, and any other procedures they might have had done.

Further showcasing our hyper-fixation on women’s appearances, a plastic surgeon posted a TikTok video in which he was challenged to look at photos of women on Love Island, guess their age and what procedures they’ve undergone, and then react to their real age. Now, I don’t want to pretend like I’ve never used someone’s looks as a way to guess how old they are. It’s completely natural. Our brain loves to use information delivered by our five senses to fill the gaps in our knowledge. Even so, there are real arguments to be made as to why society is so obsessed with evaluating a woman’s physical appearance vis-à-vis how old she is.

Personally, I don’t even think that the women on Love Island look bad. Sure, they may not look like what today’s average 20 year-old looks like. But that can be attributed to their sporting similar fashions of earlier generations, from their hairstyles down to their make-up. I mean, how many of us have perused our parents’ yearbooks and made comments like “Whoa mom, that was you at 21?” “Dad, you were my age in this photo. Why did you look like you had a life insurance policy, a car in the shop, and a third baby on the way?”

Because we see the older generations carry themselves a certain way, we then make a connection between these external presentations and maturity. Online, you see the same connection being reinforced. Fashion girlies often suggest fits that lean towards the more conservative style of our parents and grandparents (I’m talking blouses and midi skirts) when they’re curating looks that help one appear more “grown-up.”

Relating these to the women on Love Island, it’s important to note that, before the democratization of botox and fillers, these procedures’ main demographic used to be wealthy women ages 40s, 50s, or 60s and up. So, because we’ve associated botox and fillers with older women for the longest time, it’s not surprising that we automatically assume that anyone who’s gotten them done also belongs to this specific age bracket. And when you also factor in the top down, trickle down function of fashion, which simply means that the lower classes will always adopt higher class fashion as a means of upward social mobility, it becomes even more understandable why botox, fillers, and other cosmetic procedures have become as widespread as they are today.

However, any woman who is chronically online will notice that the beauty standards are changing again; that the villainization of these Love Island girlies actually points to another evolution of society’s definition of beauty. And, unfortunately, I fear that what is coming for us is a beauty standard that is even harder to attain. Because whereas the girls of 2010s simply needed to over-bake their face to join the ranks of “beautiful women,” girls today are heading into a more expensive route: one of overpriced skincare, procedures, supplements, and practices that seem to have grown their own cult following, such as red light therapy and ice baths. And as if the glorification of these thousand-dollar routines isn’t enough, there also seems to be a lack of ownership, with women who participate in them now attributing their looks to genetics. It doesn’t take an Einstein to deduce why that’s toxic.

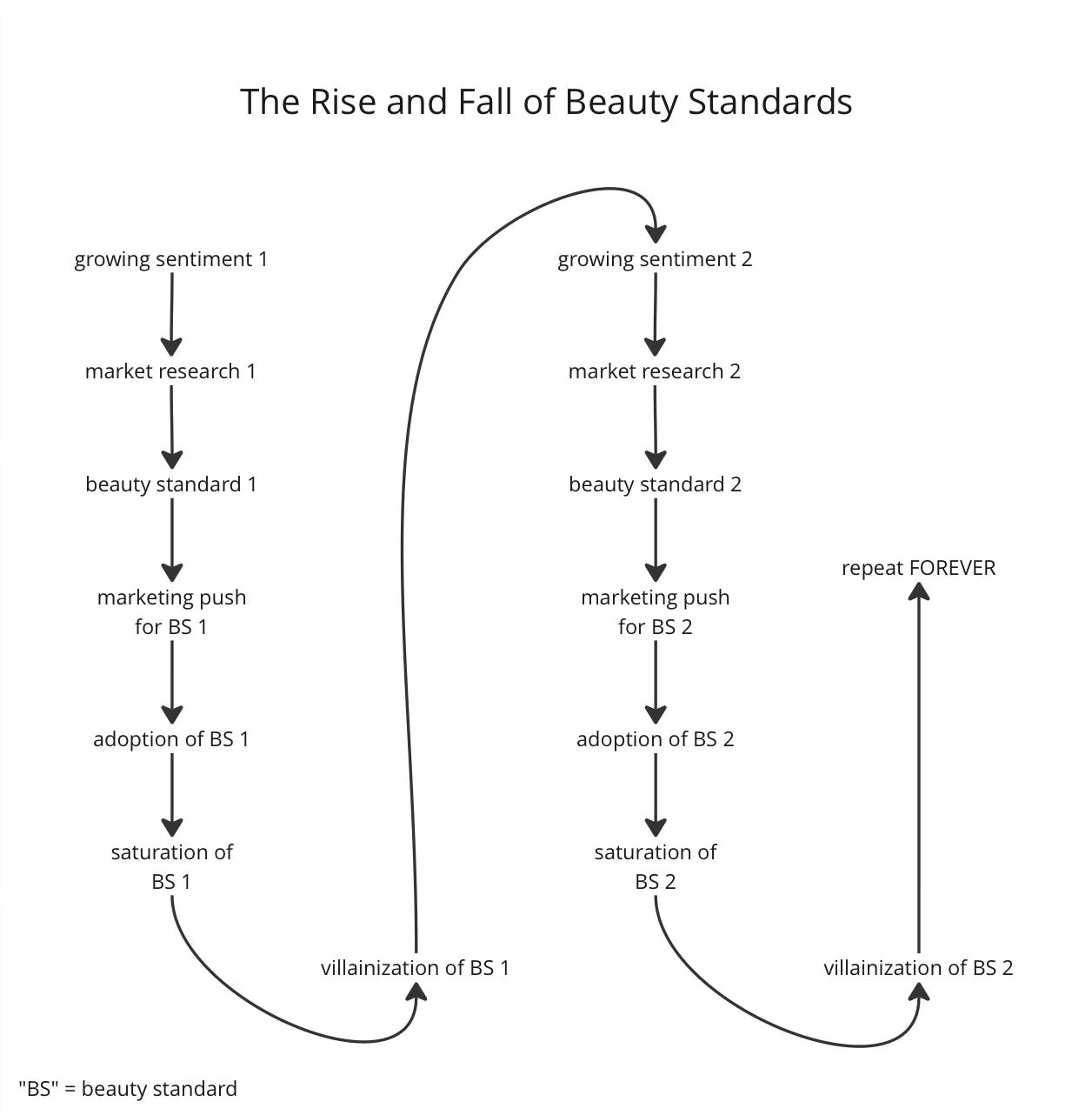

The Cycle of Unrealistic Beauty Standards

The point of this newsletter isn’t to shame women who do (or do not) get anything done. Rather, I’m calling out the unfair treatment of these women who, in my opinion, are merely victims of unfair beauty standards. These women go to all these lengths trying to look a certain way. And when they get it wrong or the standards go out of fashion, they are made fun of by the same people whose consumption habits signaled to these women what level of beauty made them worthy of attention, respect, success, and love. And I don’t know about you, but if I spend thousands of dollars and endure painful recovery only for people to mock me because they’ve decided that they no longer find pretty all the features they used to criticize me for not having, I would probably enter my villain era.

Unfortunately, ridicule knows no gender. Women are just as involved in this mockery of other women who have undergone cosmetic procedures, doling out snarky comments like “What are these women doing to their faces? I can never!” without realizing that doing so perpetuates the same harmful beliefs of the patriarchy that they’ve also sworn to dismantle.

And before you No Nuance Nellies come at me about not holding famous women accountable for perpetuating unrealistic beauty standards, I want to point out that, when it comes to issues deeply rooted in sexism, no one should be viewed as any less of a victim just because they also perpetuated in the same evil that victimized them.

To illustrate, let’s take a look at the cycle of unrealistic beauty standards.

As you can see, the emergence of beauty standards starts with a “growing sentiment,” usually informed by the elite or high-status groups. Researchers and marketers then pick up on that sentiment and work to not only fuel it until it’s become a beauty standard but also strategize how to market it to the rest of us average joes until enough of us have adopted it. However, when they deem the beauty standard as having become too saturated, the high status people who had initially informed the trend eventually decide that they do not want to be associated with the people copying them. So, what do they do? They pivot. They villainize the beauty standard, shed it like old skin, and start a new growing sentiment. And the cycle repeats itself.

The Elite and Industry’s Role in Influencing Beauty Standards

Though our smartest course of action is to focus on improving the funnel through which we receive these messages from above, I believe that it’s also worth looking into how members of the elite and industry can still find themselves in the thick of the standards they set and perpetuate.

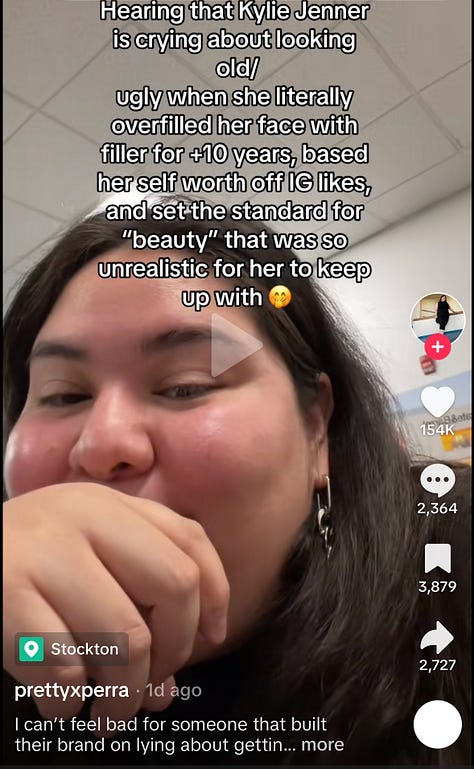

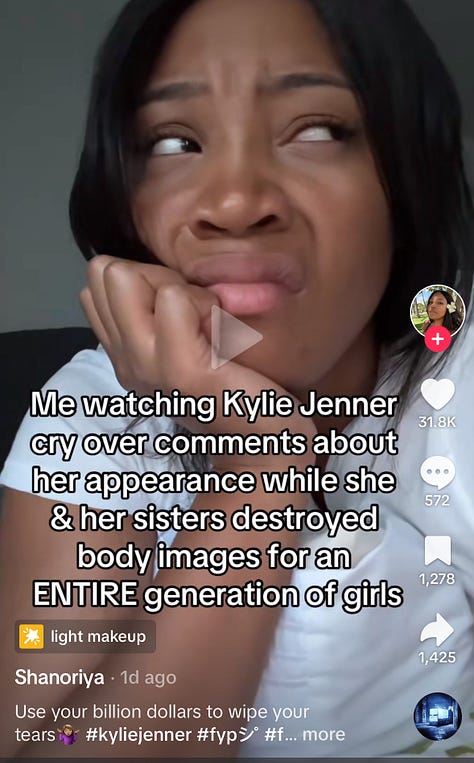

Take Kylie Jenner, for instance. In a recent episode of The Kardashians, Kylie broke down crying over criticism of her looks

She shares:

“I went on a journey last year dissolving half of my lip filler. I hate even having this conversation over and over and over again. It feels like it’s a waste of my breath because I think, with me, it is never going to change… People have been talking about my looks since I was 12 or 13 before I even got lip filler… I hear nasty things about myself all the time. I think it's just after 10 years of hearing about it, it just gets exhausting… I do think of myself as a confident person… but I'm also human, and there's only so much someone can take.”

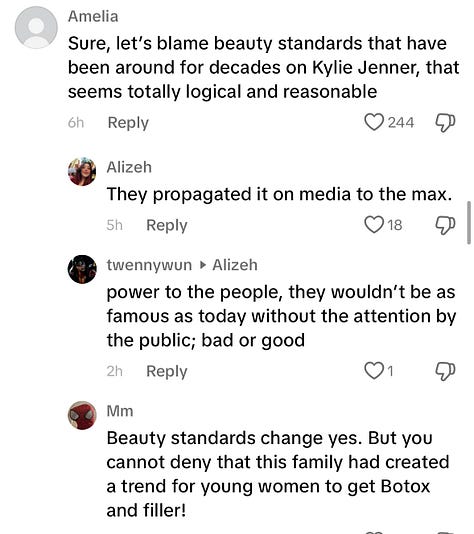

And, surprise surprise, the Internet had a lot to say.

Like the beauty industry, the cosmetic surgery industry also bears similarities to the military industrial complex. You created the beast, so you’re responsible for feeding it. Need I remind everyone though that while people are busy dancing around the flames engulfing Kylie simply because she lit her own match — even though we should probably be asking who placed the match in her hands, in the first place — there is a male plastic surgeon who is receiving positive feedback on his videos about how “old and ugly” the women on Love Island UK are.

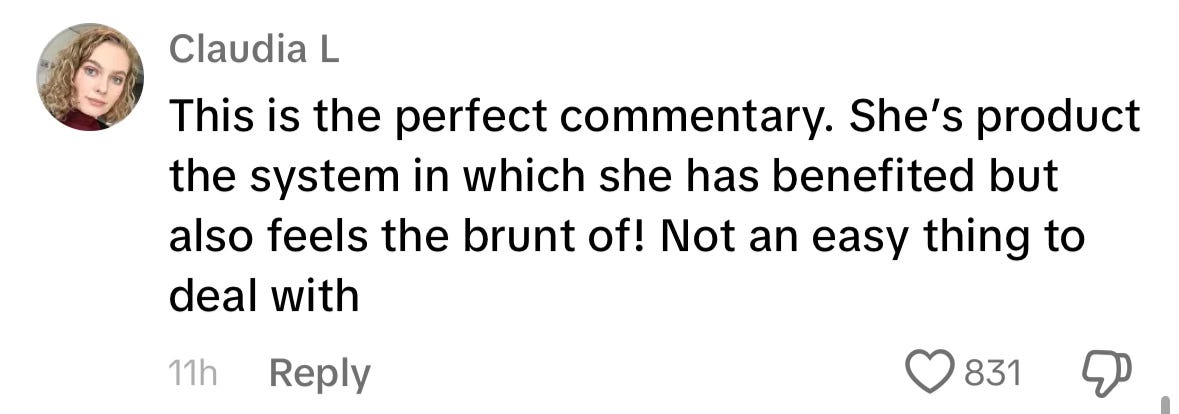

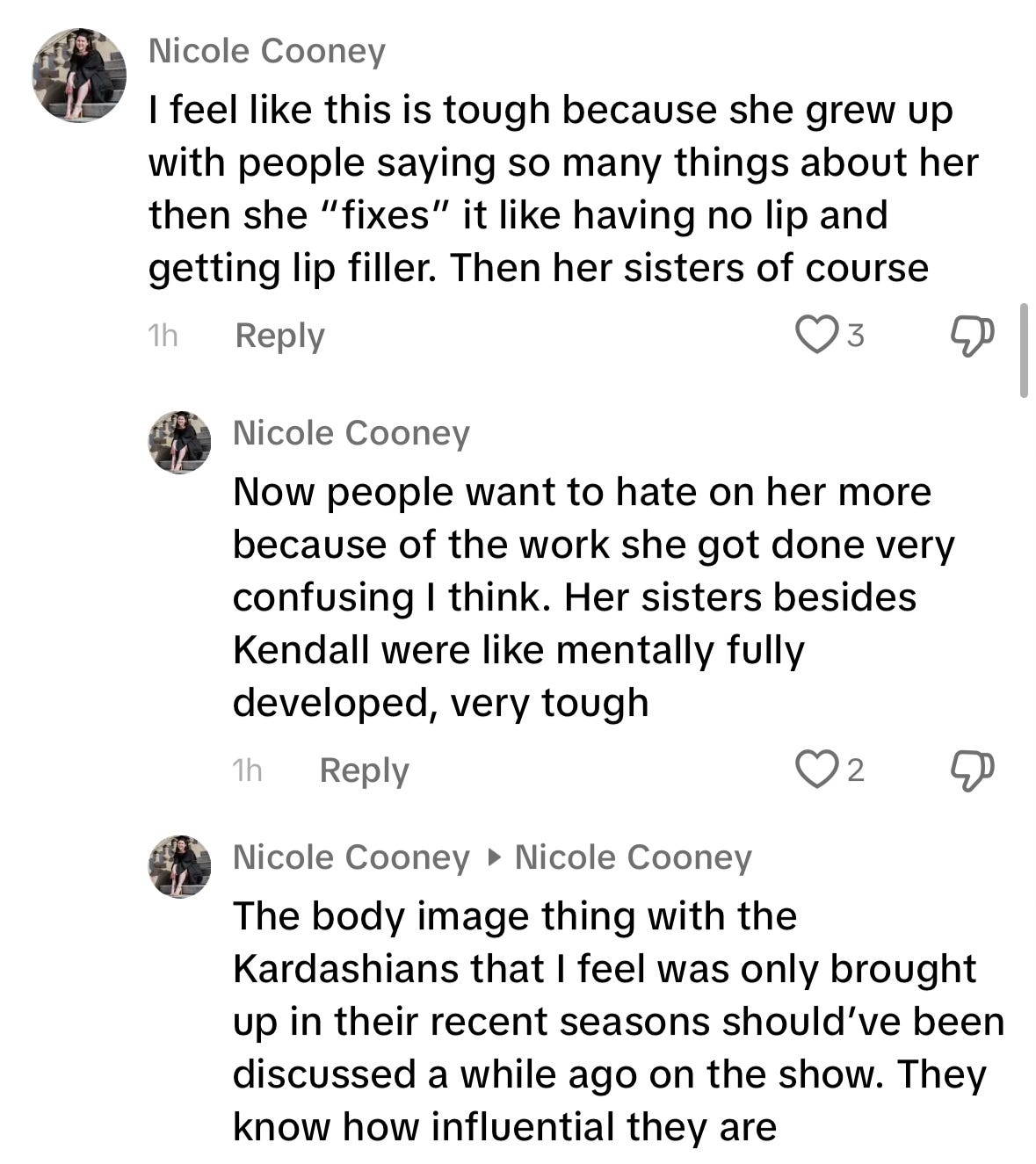

Thankfully, not everyone is convinced that Kylie doesn’t deserve even an ounce of our sympathy.

As women, we’re expected to live in this limbo state of self-acceptance and self-validation because we are made to use others’ perceptions of us as the basis of our self-esteem. But like I’ve stated earlier, it’s absolutely possible to be affected by the very thing you perpetuate. Personally, the bigger question I would rather ask is whether or not us women actually have a choice when it comes to participating? If Kylie was born to a different family, or if their family was never pushed into the limelight at this level, would she still have done to her body what she has so far?

Let’s bring it closer to home. What about us? Can we confidently say that we would behave differently and see ourselves differently if men weren’t in charge? Is the patriarchy really the only vehicle for these beauty standards to reach us? Without it, will we really be free of new versions of beauty standards? Of behavior standards?

Of standards, period?

Considering that humans organize into groups for survival and that social cohesion is created by the simultaneous inclusion of people similar to us and exclusion of dissimilar people, conformity seems to be ingrained in our species’ DNA. If we lived in a vacuum then perhaps we can opt out of conforming. But we don’t. Ironically, even those who think they’re distancing themselves from particular subgroups are forming their own subgroup. The I-could-never-do-that-to-myself women are still creating a community founded on othering and excluding other women who have chosen to get things done.

Is Individuation the Future?

It is not news that the choices we make over our own bodies affect how others see their own bodies. In fact, Kylie Jenner herself has expressed fear over her daughter Stormi following in her footsteps. Opening up about her regrets about getting breast implants at 19, Kylie shares:

“I don’t want my daughter to do the things I did. I wish I’d never touched anything to begin with… I would be heartbroken if she wanted to get her body done at 19. She’s the most beautiful thing ever. I want to be the best mom and the best example for her. I wish I could be her and do it all again because I wouldn’t touch anything.”

The same sentiments are echoed in “Eight Bites,” a short story in Carmen Maria Machado’s collection entitled “Her Body and Other Parties.” In the story, a narrator is set to get gastric bypass surgery in order to feel full faster and consequently lose weight easier. The narrator’s daughter is against the procedure and tells her mom over the phone:

“Do you hate my body, Mom?” she says. Her voice splinters in pain, as if she were about to cry. ”You hated yours, clearly, but mine looks just like yours used to, so—”

We don’t even have to look very far to see this relationship between our self-image and that of other people. From our mothers to our friends, those closest to us are indirect recipients of our self-criticisms. How can we expect our mother to feel beautiful when we want to alter the nose that resembles hers? How can our best friend feel good about the rolls on their stomach when all we talk about is how much we want to get liposuction done on ours?

We play a role in this never-ending, increasingly unrealistic beauty standard cycle. But if we can wake up to that role and exercise more mindfulness about how we move within it, maybe we can build a future generation of women who wouldn’t feel the need to go under the knife to conform to beauty standards. A generation of women who do not blindly live for the validation of others as in collectivism but are also not self-centered as in individualism. A generation of women or, well, people who value individuation instead — the middle ground that reconciles human beings’ monkey see, monkey do tendencies and the need for deeper appreciation for what makes each of us unique.

Beauty Standards are There to Keep Us Tired

I have always found it suspicious that beauty standards seem to change when women are on the cusp of the next level of liberation. Now that birth rates are dropping, and women are leaving men behind and dominating higher education, word suddenly breaks out that BBLs are out and skinny is back in. It’s almost as if the schedule of when these changes are broadcasted is designed to ensure that women remain “in their place.” Never thinkers and doers in society, always just pretty things on display.

But as spoiled girlies, we don’t get mad. We get paid. We see the world purely for what it is and play the game by our own rules.

So, when you encounter another new beauty standard, ask yourself:

How badly do I need to conform to this one?

Will I get paid for conforming?

Do the benefits outweigh the risk? Does the investment?

What are the long-term effects?

Unfortunately, we still live in a world that loves to harshly judge a woman’s appearance. But imagine if women collectively decided to become more mindful of our role in the rise and fall of beauty standards, pulling on levers until the scales tip in our favor. Remember: the only thing we have complete control over is ourselves. So, let’s change how the game is played on our level. Let these people who influence, pioneer, and promote beauty standards find out that we are finally embracing our diverse versions of beauty.

If we’re serious about diversifying, de-centering, and decolonizing beauty standards, then we have to act like it and consume like it. We have to, in our own ways, claim ourselves as the new beauty standard. We don’t need a movement, a catchy slogan like #MeToo, a pretty Instagram page with quotes and affirmations. The next time they push a new standard upon us, don’t engage. Let’s show them that it’s not even worth our time. They know our attention is currency, and they’ll crumble when we finally learn how and where to spend it.

So wake up, bestie.

The bad news is we all have a role to play in this cycle. The good news is we all have a role to play in this cycle! Instead of exhausting ourselves trying to influence these elites and industry people (I mean, you can still try), we can take ownership of our role and work to be better consumers of media, goods, and ideas. Hopefully, when we shift from being mindless followers to more engaged and critical participants in society’s exchange of ideas, the people at the top are forced to do better because they also depend on us to consume their products, avail their services, and keep the economy going. Like I’ve always told the spoiled girlies in the spoiled girlie support group, “don’t get mad; get paid.”

-Elle